As with nickel, seasonality today is a minor driver of other base metal’s prices, but mine production is just as historically dependent on the time of the year.

In the last article, I wrote about the significant drop in nickel price seasonality. At one time ±16% of the price of the metal was down to which month it was purchased, but today seasonality accounts for little more than ±3%.

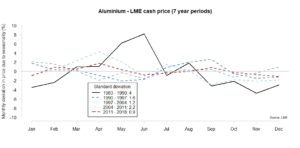

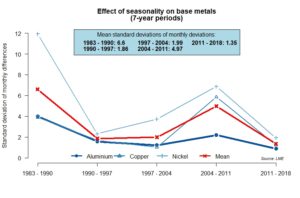

A similar pattern exists for the other major base metals – Aluminium and copper:

Both metals see the same change in standard deviations of monthly price:

- From the high point in the first 7-year period, there is a decrease in volatility as financial and logistics tools, such as warehouses, become ever more established.

- A rise over the first decade of the 20th century, as buoyant Chinese growth bring periods of tightness, which are magnified by increased financial speculation.

- A drop to some of the lowest levels, as Chinese demand growth slows, coinciding with the end of much-discussed ‘commodity supercycle’.

It’s true that copper seasonality was lowest in the period 1997-2004. This reflects a time when there was strong acceptance of hedging instruments for copper, but the forces that brought seasonality had yet to surface. The London Metal Exchange (LME) was founded on copper contracts in 1877, while aluminium contracts were only introduced in 1978.

Showing the three metals, and the conclusion is clear: Seasonality today is a fraction of the driver of base metal prices it has before.

It would be much more insightful to look at short-term effects, like labour strikes or trade policies, and long-term drivers, like demographics and the substitution of aluminium-cored wire for copper wire, to understand base metal prices, than to look at the calendar.

…but not production seasonality

However, despite the lack of price seasonality, production is affected by the time of the year. Chile, the largest copper miner, accounted for 27.1% of mined copper in 2017. The chart below uses the same methodology as the price seasonality charts, but shows production seasonality. Here volatility has stayed at much the same level over the years.

This mismatch between price- and production-seasonality can be attributed to the smoothing effects of today’s financial and logistics tools. Further, I would argue that this mismatch is positive for the supply-chain. Divorcing seasonally-affected production from seasonally-unaffected price fluctuations allows companies to make better financial plans, to more easily achieved financial hurdles and to report stronger control of cash-flow. Without these tools, projects and manufacturing would be less profitable, due to the extra risk that would need to be priced in, and with a corresponding hit to global GDP. So, diminishing the effectiveness of metals exchanges, like the LME, would have a negative influence on the world’s economy.

For the next article, I will analyse the price of energy commodities, to see if here seasonality is a price driver and the reasons for any differences.