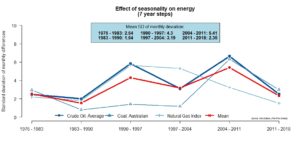

The demise of annual contracts roils pricing and brings increased seasonality

While base metals have seen a sharp drop-off in seasonality, due largely to better logistics and the availability of financial contracts, the same is much less true for energy markets.

As the graph above shows, energy commodities have seen differing seasonality, but generally increasing. Previously, prices for many energy commodities were fixed annually. Though the growth of short-term contracts and the oft significant discount between annual contracts over spot prices means few contracts are now set annually. This has brought seasonality, where previously there was little to none.

Australian coal stands out as a clear indication of how prices have developed. The prices of many types of coal were set on annual fixed contracts from the 1980s through to late 2000s. With the bulk of coal sold on annual contracts, as energy producers needed to guarantee both their supply and price, the impact of seasonality was limited to once a year for contracted tonnage.

As demand from China rose, the annual contracts, often fixed with European or Japanese buyers, became less pertinent, and coal moved from annual contracts to shorter-term contracts. Usually quarterly, but based on the recent spot prices. Previously accounting for a few percent of the price of coal, it rose to account for 12%. This has started to diminish as Chinese demand is better understood and other commodities take market share, but it is still significantly higher than when annual contracts dominated.

The same but more prononuced pattern is clear in iron ore. As with Australian coal, iron ore was set once a year for annual contracts. This cosy pricing setting ended in 2010 when Chinese steel producers, who had become significant purchasers but typically on spot markets, refused to have their price dictated by other producers. Annual pricing went out the door, and quarterly pricing, set on past spot prices, became de facto methodologies.

From these two commodities it is apparent that the movement away from annual contracts to quarterly or spot pricing brings increased seasonality. This is also often accentuated by the effects of unexpected events, such as typhoons off Australia or demand spikes in China. However, unlike with base metals, purchasers have a lack of instruments to hedge exposure. This is a headache for purchasers, who often have variable input costs, but fixed prices for their goods.

From these two commodities it is apparent that the movement away from annual contracts to quarterly or spot pricing brings increased seasonality. This is also often accentuated by the effects of unexpected events, such as typhoons off Australia or demand spikes in China. However, unlike with base metals, purchasers have a lack of instruments to hedge exposure. This is a headache for purchasers, who often have variable input costs, but fixed prices for their goods.

So, while the coal and iron ore markets are unlikely to move back to annual pricing purchasers are looking for both surety of supply and stability of price. Miners are able to provide the first, but the second is difficult without a significant price premium to cover fluctuations. For now, purchasers are often forced to buy with variable prices, and the hope that price surges are not so large as to remove the margin on their products.

In the last article in this series, I will look at agricultural products. These are the definition of a seasonal commodity and the first instigators of contracts to avoid seasonality. How have the foodstuff markets overcome the problems of seasonal production and are there any lessons for base metal and steelmaking raw materials purchasers?