I regularly write about commodities and the forces driving supply, demand and price. Normally, there is lots to write about on market drivers and unexpected events like tariffs, strikes or weather. However, when the market is slow and developments are few, there is always ‘seasonality’ to fall back on for a paragraph.

Seasonality comes from events like demand cycles and events like Chinese Golden Week, Thanksgiving and Christmas. For a commodity, like steel, construction in the northern hemisphere is typically strongest in the second quarter, so prices rise, and slows for summer holidays around July and August. Similar patterns should be apparent in all commodities.

While a stalwart of slow-writing periods, my analysis shows that the relevence of this seasonality is waning. The differences between months is diminishing and no longer a strong driver of prices.

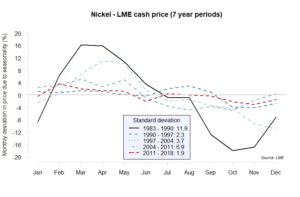

To start, I looked at the LME nickel spot price between 1980 and July 2017. Using R, the statistical language, I decomposed the monthly seasonality of 7-year periods, but the same findings are true irrespective of the period. The results are illustrated below.

To quantify the degree of seasonality in each of the period, I calculated the standard deviation of the monthly differences. The standard deviations dropped sharply in the decade before the millennium, rose again in the first decade of this millennium, and then fell sharply to their lowest level.

The initial fall can be seen as a reflection of growing availability and trade in financial instruments. For example, in the 1980, Norilsk Nickel was a major supplier of nickel, but being based in Siberia had difficulty shipping its nickel due to challenges of winter on logistics. Prices rose, and then fell when material could flow. Improving infrastructure made trade easier. At the same time, the London Metal Exchange (LME) introduced its nickel contract in April 1979. As the contract gained acceptance, buyers and sellers could smooth their trade in nickel, and so seasonality reduced.

The return of seasonality in the period 2004-2011 is related to the growth of base metals as an asset class. In 2007, Jim Rogers released his book, “Hot Commodities: How Anyone Can Invest Profitably in the World’s Best Market”, which helped to further intensify the focus of financial markets on base metals. The LME contracts for base metals were increasingly used by speculators magnifying any market tightness, including seasonal effects.

Finally, seasonality has dropped off sharply in the last period, as legislation and low margins have stunted the speculator market for base metals, with many financial institutes closing their commodity departments. With mainly industrial players active in the market and the growth of tools to hedge exposure, there is now limited differences between the months.

In conclusion, with the growth of financial contracts, improved warehouses and the recent move away from base-metal speculation, seasonality has been effectively suppressed. Neither sellers nor journalists should be able to use seasonal differences to explain notable market developments. While, the timing of some holidays, most importantly Golden Week, will have an effect on the month they are celebrated, which commentators should reference, historic seasonality is now a minor driver of nickel prices.

In the next note, I will look at other base metals, and then other commodities.